I’ve observed hundreds of ESL and other small-format classes over the years, and one thing that always interests me is the pattern of interaction between the teacher and the students. For years there has been an injunction against ‘teacher talking time,’ and class observers commonly pointed out (and still do) when the teacher is talking too much, lecture-style. You can represent this type of classroom interaction in the following way (forgive my back-of-the napkin doodles):

In this interaction pattern, information is being communicated one-way, from the teacher to the students. At least you hoped communication was happening: that would depend on whether the students were listening, or tuned out. (Lecturing can be a useful teaching method, used in moderation. You just have to be an excellent lecturer, able to hold students’ attention for a prolonged period of time. Not many of us really have this talent.)

More commonly in classroom observations, I would see – because the teacher was likely making a special effort to ‘get the students to talk’ – a more socratic-type interaction that looked more like this:

Nonetheless, the interactions were still limited to what looked like a series of one-to-one conversations between the teacher and each student. I would often notice that other students’ attention drifted during these types of interaction.

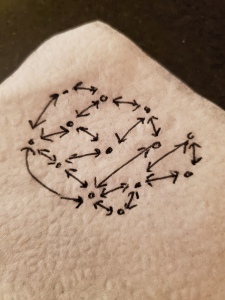

What these interaction patterns failed to do was to do what I call ‘exploiting the interactive potential of the classroom.’ Meaning that when you have a group of people gathered together in a room, you have a unique opportunity for learning to take place by having those people interact with each other. This could result in various configurations such as this:

Or this:

The interaction patterns I’ve described represent a shift from a ‘banking’ model of education, in which knowledge is supposedly communicated by a fount of all knowledge to students lacking knowledge and with nothing to contribute to the educational enterprise; to a constructionist model, in which knowledge is not transmitted but grows or is built in the mind and behaviors of each learner.

(Scheduling observations with a teacher was interesting when the teacher would tell me, “Don’t come on Tuesday, the students are just giving presentations.” Or, “I’m just having the students work in groups for most of the class, so you won’t be able to see much.” The assumption being that if the teacher was not up there ‘performing,’ there would be nothing interesting to see.)

With advances in technology and recent notions about the ‘flipped classroom,’ there is less and less excuse for classroom interactions to be teacher-dominated. To give an example from the 1990s: I used textbooks that contained listening and speaking exercises based on NPR stories that could be between five and ten minutes long. Typically the instructions in the textbook called for the students to ‘listen to the story’ for general information. Then ‘listen to the story again’ for details. And finally ‘listen once again’ for some more specialized task. I could never help but feel that a lot of class time was being wasted by students just sitting there listening (hopefully) to the story. It did help to fill the time in my lesson plan though, even if it did suck the energy from the room in those drowsy early afternoon hours. (By the way, the shall-not-be-named textbook that contained not-very-interesting-and-wholly-unrealistic 15-20 minute ‘college lectures’ was the greatest offender.)

The problem was that the story was recorded on the book’s copyrighted cassette (later CD) which was made available only to the teacher (emphasizing the banking model’s notion of the teacher as holder and distributor of knowledge). The only legal way to distribute the story to the students was in the classroom by pressing ‘play.’

These days, textbooks – and enterprising teachers who pull material from the internet – make it possible for students to access the listening material themselves, in their own time, and play and re-play it (in some cases at the speed of their choice) as many times as they wish. And the increasingly popular learning management systems and published online materials allow students to do much of the individual work on their own. This means that the teacher is able to truly exploit the interactive potential of the classroom by having students get their language input outside of class. One principle I learned early on in my career was, “Don’t let students do in class what they could do outside of class.” The thing they have difficulty doing outside of class is working with each other, discovering and building knowledge together. And if I went to observe a class today, that is what I would want to observe. How does the teacher create the right conditions for learning, recognizing that the classroom is potentially an interactive environment?

But for all our talk of ‘student-centered learning,’ I’m afraid that if you walk past many ESL classrooms on a typical day, the most likely thing you will hear is the teacher’s voice. You might still hear the listening text from the textbook (often a TED Talk these days). In some cases, more egregiously, a movie is being shown – which makes that classroom the most expensive movie house in town.

Now I may have gone a bit too far here. Running an interactive classroom has its challenges. If you, the teacher, expect the students all to have done their out-of-class listening, reading, or exercises and to be ready to discuss them in class, you may be disappointed. Even if you train your students to do all their out-of-class preparation, you know that some won’t have done it. In those cases, you have to decide what to do with the slackers – try to incorporate them anyway, or set them aside to do the work they should have done and assign a lower grade?

Despite the challenges, if teachers are not exploiting the interactive potential of their classrooms, they are failing to keep up with established good practice, and denying their students a once-only opportunity. Classroom interaction should be high on the ‘classroom observation checklist’ for anyone observing or being observed teaching.