We’ve been hearing more and more about companies requiring employees to return to work at the office now that the COVID-19 era work-from-home mandates are no longer so compelling. There is pushback from many employees, who argue that they are more productive at home and appreciate freedom from the daily commute that wears on them and causes traffic congestion and pollution. For their part, companies argue that in-office work results in greater productivity and collaboration among employees. Possibly the relative effectiveness of in-person and remote work depends on the type of business. While a purely digital company like Dropbox has a ‘virtual first’ policy, allowing employees to work 100% remotely, some high-profile corporations such as Amazon and Google are requiring in-person attendance. Amazon’s justification is that in-person work “will strengthen company culture, collaboration, and mentorship” (1). On its hybrid three-days-a-week-in-person policy, a Google spokesperson stated, “(i)n-person collaboration is an important part of how we innovate and solve complex problems.” (2).

In performance-based workplaces that are common in the U.S. and many other industrialized countries, there is a strong emphasis on individual productivity, performance, and achievement. Ambitious employees strive for recognition in order to get ahead, and performance evaluation systems recognize merit based on the achievement of individual goals. Managers rightly try to motivate employees to do their best work, and identify, recognize, and reward the strongest contributors.

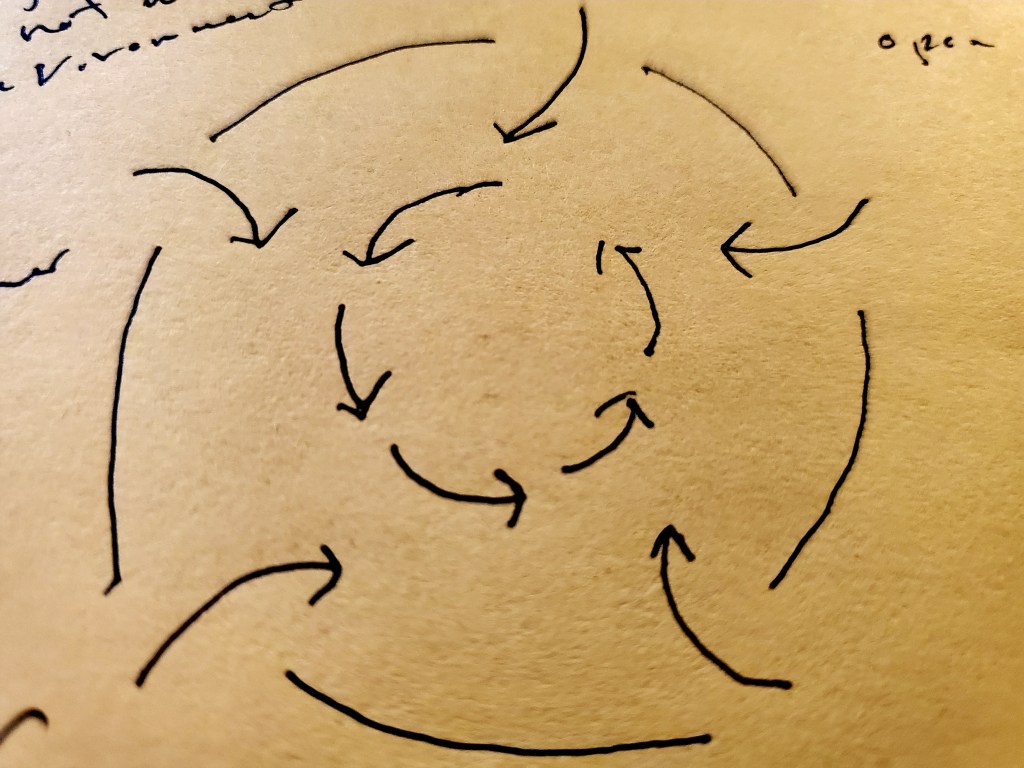

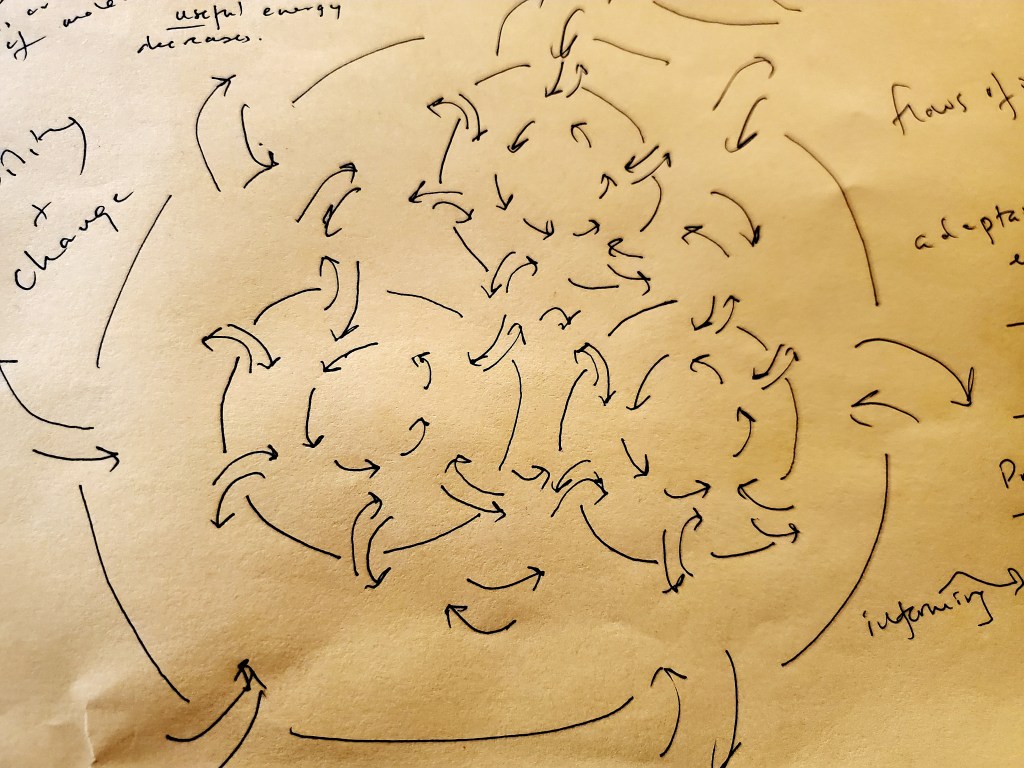

This isn’t where the manager’s role ends, though. Most organizations – and schools are a good example – don’t thrive through the isolated efforts of individuals, but through the joint work of people in collaboration, which is more than the sum of the parts. If an organization is in any sense like a machine (but let’s not stretch this analogy too far), then we know that the individual parts of a machine are useless on their own. It’s only when the parts are working together as part of a system that the machine functions. A big piece of the manager’s job is to ensure that the system – not only the individuals in it – is functioning correctly. This involves what I call ‘managing in the gaps,’ because it is about what happens in the spaces between and among the individual employees. When relationships are positive and there is collaboration, the team, department, branch, or organization is effective. Many problems organizations experience arise when relationships between and among individuals and teams are poor or not well developed.

Managers cannot simply trust that good relationships will arise in the workplace, and they should assume that at least some relationships between individuals and teams will be problematic. Even with great individuals on board, workplace setups can create friction that get personal. For example, at one intensive English program, it was one staff member’s job to provide administrative support to faculty coordinators of short and specialized programs. But because roles hadn’t been clearly demarcated, disputes frequently arose between the staff member and the coordinators over whose responsibility certain tasks were. The individuals involved were strong and positive employees who wanted to do a good job, but the situation inadvertently put them into conflict with each other, and yes, it got personal. It was the manager’s job to recognize the source of the tension and develop a solution, which in this case was to define and explain each person’s role more clearly, and follow up to make sure everyone involved understood. That done, relationships improved and programs could be delivered more effectively. This is an example of managing in the gaps.

Managing in the gaps isn’t only about troubleshooting problems, though; it’s primarily about preventing them from arising in the first place. Although it’s easy to criticize workplace meetings with slogans like ‘death by meeting’ and complaints such as, ‘I just want to get out of meetings and on with my job,’ there is a lot to be said for regular team check-in meetings and cross-department check-ins to hear what others are doing, share stories about what’s working or not, anticipate potential obstacles and plan around them, and just engage with each other face to face as people. Meetings like this don’t need a strict agenda, but should allow participants to share with others what’s going on in their job or area of the organization. Think of meetings like this as like bringing in your car for a regular oil change and tune-up. Again, the individuals in the organization may be doing a great job, but managers need to address the effectiveness of the whole.

While some online, work-from-home organizations have developed sophisticated means for the kind of relationship development and collaboration described here, people-centered organizations such as most schools don’t tend to lend themselves to the kind of collaboration needed to make the whole thing work remotely. From what we know about interactions on social media, at their most extreme people can become pretty nasty to each other when they don’t know each other or interact face to face. We are human, and most of our great achievements have come not from individuals working in solitude, but from doing things together, in relationship to each other. Some employees may argue, “I’m more productive working on my own at home,” and that may be true individually, but it’s what the team achieves – not the individual – that ultimately determines the fate of an organization.

Are you managing in the gaps? Here are six quick questions to check:

- When tensions arise between people or teams do you try to look beyond the individuals involved and consider the system that has put them into conflict with each other?

- Do you openly appreciate or celebrate collaboration among individuals and teams?

- Do you hire people based not only on their ability to do the tasks associated with their position but also on their ability to work with others?

- Do you evaluate, and reward people on the same basis?

- Do you regularly gather individuals on a team to check in on how things are going, even without a specific agenda?

- Do you call regular meetings of two or more teams to share what everyone is working on?

Make it a habit to pull back from the individuals – and from the individual team – and look for solutions in the gaps.

unimagined ways, but right now many educators face the immediate problem of how to respond appropriately to students’ use of ChatGPT, which can produce passable text and images in multiple genres and formats. What are we to make of this new resource and its place in education? Is ChatGPT a threat to academic integrity or a tool that teachers and their students can leverage to achieve better performance?

unimagined ways, but right now many educators face the immediate problem of how to respond appropriately to students’ use of ChatGPT, which can produce passable text and images in multiple genres and formats. What are we to make of this new resource and its place in education? Is ChatGPT a threat to academic integrity or a tool that teachers and their students can leverage to achieve better performance?

When I create an I-20 form for a prospective student, the SEVIS system has me choose “Language Training” as the student’s area of study. I’m always intrigued by this choice of words. Why is learning English considered ‘training’ and not ‘education?’ Are other disciplines – math, the sciences, English literature and foreign languages – considered to be training?

When I create an I-20 form for a prospective student, the SEVIS system has me choose “Language Training” as the student’s area of study. I’m always intrigued by this choice of words. Why is learning English considered ‘training’ and not ‘education?’ Are other disciplines – math, the sciences, English literature and foreign languages – considered to be training?

colorful mailings from colleges in our mailbox every day. It’s a competitive market for students, and college marketing offices need to make their institutions attractive.

colorful mailings from colleges in our mailbox every day. It’s a competitive market for students, and college marketing offices need to make their institutions attractive.  If you’ve been teaching English as a second or foreign language for a few years, you’ve probably taught using a wide variety of textbooks. Over the years, textbooks have evolved from layouts you could easily create (now anyway) in Microsoft Word, to sophisticated, full-color extravaganzas that seem designed to cater to limited modern attention spans. Textbooks also mirror evolving approaches to language teaching, from the decontextualized sentences of grammar-translation, through the drill-and-kill repetitions and substitutions of audiolingualism, information gaps and situational dialogues of communicative language teaching, to…whatever it is we have now, which is not entirely clear.

If you’ve been teaching English as a second or foreign language for a few years, you’ve probably taught using a wide variety of textbooks. Over the years, textbooks have evolved from layouts you could easily create (now anyway) in Microsoft Word, to sophisticated, full-color extravaganzas that seem designed to cater to limited modern attention spans. Textbooks also mirror evolving approaches to language teaching, from the decontextualized sentences of grammar-translation, through the drill-and-kill repetitions and substitutions of audiolingualism, information gaps and situational dialogues of communicative language teaching, to…whatever it is we have now, which is not entirely clear.

Assigning final grades to students has been done in various ways over the years. In some contexts, everything rested on a final exam – this was the case with the O-level and A-level exams I took in a British high school ‘back in the day.’ Then ‘continuous assessment’ became popular, making the final grade a composite of grades for assignments completed during the course, either with our without a final exam. This approach became popular in U.S. intensive English programs, where the final grade might be made up of homework assignments, projects, tests and quizzes, and the usually ill-defined ‘participation’ by the student.

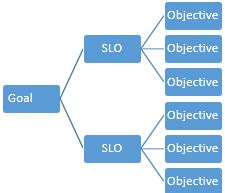

Assigning final grades to students has been done in various ways over the years. In some contexts, everything rested on a final exam – this was the case with the O-level and A-level exams I took in a British high school ‘back in the day.’ Then ‘continuous assessment’ became popular, making the final grade a composite of grades for assignments completed during the course, either with our without a final exam. This approach became popular in U.S. intensive English programs, where the final grade might be made up of homework assignments, projects, tests and quizzes, and the usually ill-defined ‘participation’ by the student.  If you’ve had anything to do with curriculum over the past few years, then you’ve likely wrestled with the terms ‘goal,’ ‘outcome,’ and ‘objective.’ It’s not surprising they cause confusion. After all,

If you’ve had anything to do with curriculum over the past few years, then you’ve likely wrestled with the terms ‘goal,’ ‘outcome,’ and ‘objective.’ It’s not surprising they cause confusion. After all,

programs, whether teachers or staff, are extremely kind, generous with their time and attention, and committed to their students. You’d think in an environment with people like that, students would always be well served. But in some cases the organization is set up in such a way that good student service is impeded. Here are three examples of organization-level problems and a suggested approach to addressing each one.

programs, whether teachers or staff, are extremely kind, generous with their time and attention, and committed to their students. You’d think in an environment with people like that, students would always be well served. But in some cases the organization is set up in such a way that good student service is impeded. Here are three examples of organization-level problems and a suggested approach to addressing each one.

In 1939, the American writer Ernest Vincent Wright published a novel named Gadsby. Nothing too special about that you might think, except that this 50,000-word work of fiction did not contain the letter ‘e.’ Can you imagine even writing more than a word or two without the letter ‘e’? Me either.

In 1939, the American writer Ernest Vincent Wright published a novel named Gadsby. Nothing too special about that you might think, except that this 50,000-word work of fiction did not contain the letter ‘e.’ Can you imagine even writing more than a word or two without the letter ‘e’? Me either. It has been a quiet week for English language programs. That is something to be thankful for after the craziness that was visited on us in the first half of July, when the Department of Homeland Security issued a new rule: international students attending institutions that are going to offer their programs entirely online must either transfer to another institution where they can take at least a part of their program face to face, or leave the country. The rule of course impacted students at the hundreds of English language programs and schools across the country.

It has been a quiet week for English language programs. That is something to be thankful for after the craziness that was visited on us in the first half of July, when the Department of Homeland Security issued a new rule: international students attending institutions that are going to offer their programs entirely online must either transfer to another institution where they can take at least a part of their program face to face, or leave the country. The rule of course impacted students at the hundreds of English language programs and schools across the country. What does the future hold for English language programs in the U.S., once we get over the current crisis caused by the COVID-19 virus? Will things return ‘to normal,’ with students traveling here to study at English language schools and university-based programs? Or will a wholesale rush to online learning result in the virtual disappearance of in-person programs?

What does the future hold for English language programs in the U.S., once we get over the current crisis caused by the COVID-19 virus? Will things return ‘to normal,’ with students traveling here to study at English language schools and university-based programs? Or will a wholesale rush to online learning result in the virtual disappearance of in-person programs? The novel coronavirus has gone pandemic, our entire cohort of students has canceled, and we’ll be closed for the semester. While it’s encouraging that faculty are willing to re-tool quickly for online teaching, we are a study abroad program where English happens to be taught, and you cannot study abroad online. It’s true that many English language programs have ‘gone online’ to try and ride out the crisis, but this is a stopgap measure that will not satisfy students over the long haul. The corona crisis forces us to consider just what English language programs in the U.S. actually are, and what value they offer to their students.

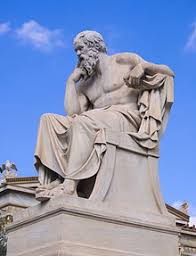

The novel coronavirus has gone pandemic, our entire cohort of students has canceled, and we’ll be closed for the semester. While it’s encouraging that faculty are willing to re-tool quickly for online teaching, we are a study abroad program where English happens to be taught, and you cannot study abroad online. It’s true that many English language programs have ‘gone online’ to try and ride out the crisis, but this is a stopgap measure that will not satisfy students over the long haul. The corona crisis forces us to consider just what English language programs in the U.S. actually are, and what value they offer to their students. Yes, a teacher asked me this recently. While her question seemed mostly an expression of frustration at what she saw as a loss of control over her teaching, it is also a question that educators should consider seriously. After all, education proceeded quite well for thousands of years without SLOs. Socrates never referred to them, nor did Jesus, the Buddha, or any other well-known teacher you could name.

Yes, a teacher asked me this recently. While her question seemed mostly an expression of frustration at what she saw as a loss of control over her teaching, it is also a question that educators should consider seriously. After all, education proceeded quite well for thousands of years without SLOs. Socrates never referred to them, nor did Jesus, the Buddha, or any other well-known teacher you could name. Back in the day, if you were ‘teaching to the test,’ you weren’t really doing your job as a teacher. You isolated the pieces of knowledge and the skills that you knew would come up on the test and taught them to the exclusion of broader educational activities that might have enriched the students’ experience. You might have done this to ensure a high pass rate, which reflected well on you as a teacher if the higher-ups were judging you on your students’ test scores. But teaching to the test was frowned upon as a kind of shortcut for both teacher and students.

Back in the day, if you were ‘teaching to the test,’ you weren’t really doing your job as a teacher. You isolated the pieces of knowledge and the skills that you knew would come up on the test and taught them to the exclusion of broader educational activities that might have enriched the students’ experience. You might have done this to ensure a high pass rate, which reflected well on you as a teacher if the higher-ups were judging you on your students’ test scores. But teaching to the test was frowned upon as a kind of shortcut for both teacher and students. How many times are ESL students told to ‘go out and speak English?’ The possibility of using the target language outside the classroom and the school is surely one of the strongest rationales for learners to come to an English-speaking country to learn the language. Theorists of second language acquisition have proposed that ‘negotiation of meaning’ with native speakers will provide learners with the comprehensible input they need to make progress, making access to native speakers important to that progress. As Bonny Norton points out in the 2nd edition of her book Language and Identity, getting that access is not so simple.

How many times are ESL students told to ‘go out and speak English?’ The possibility of using the target language outside the classroom and the school is surely one of the strongest rationales for learners to come to an English-speaking country to learn the language. Theorists of second language acquisition have proposed that ‘negotiation of meaning’ with native speakers will provide learners with the comprehensible input they need to make progress, making access to native speakers important to that progress. As Bonny Norton points out in the 2nd edition of her book Language and Identity, getting that access is not so simple.

If you read anything about curriculum design these days, or attend a presentation or workshop, you will learn only one model. Backward design starts at the end, defining student learning outcomes, then working backward through assessment, teaching and learning objectives, content and sequencing, and finally teaching and learning. This approach to curriculum design is so pervasive that anyone new to education might think there is no other way.

If you read anything about curriculum design these days, or attend a presentation or workshop, you will learn only one model. Backward design starts at the end, defining student learning outcomes, then working backward through assessment, teaching and learning objectives, content and sequencing, and finally teaching and learning. This approach to curriculum design is so pervasive that anyone new to education might think there is no other way.

Backwards-design curriculum is a relatively new approach to curriculum design that is finding its way into many disciplines. In English language teaching, backwards design originated with English for Specific Purposes courses (such as English for pilots or English for the food service industry) where it was important to specify what learners should be able to do following the course or program. In the US, it was given a boost by the accreditation requirements of ACCET and CEA, themselves subject to the mandates of a federal Department of Education that sought greater accountability from educational institutions, starting with the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

Backwards-design curriculum is a relatively new approach to curriculum design that is finding its way into many disciplines. In English language teaching, backwards design originated with English for Specific Purposes courses (such as English for pilots or English for the food service industry) where it was important to specify what learners should be able to do following the course or program. In the US, it was given a boost by the accreditation requirements of ACCET and CEA, themselves subject to the mandates of a federal Department of Education that sought greater accountability from educational institutions, starting with the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. We are used to talking a lot about quality in education. It used to be normal to describe quality in terms of inputs: faculty to student ratios, faculty degrees, school facilities, test scores of the incoming class, and so on. More recently, we have been pressured by government departments, funding agencies, and accreditors to prove our quality in terms of outcomes: can-do statements, demonstrable skills gained, behavioral changes in our students at the end of their course or program.

We are used to talking a lot about quality in education. It used to be normal to describe quality in terms of inputs: faculty to student ratios, faculty degrees, school facilities, test scores of the incoming class, and so on. More recently, we have been pressured by government departments, funding agencies, and accreditors to prove our quality in terms of outcomes: can-do statements, demonstrable skills gained, behavioral changes in our students at the end of their course or program. SEVP

SEVP

At a recent professional development session at

At a recent professional development session at

Most intensive English programs offer a placement test or a set of procedures to try and ensure that students are receiving instruction at an appropriate level. Minimally, a multiple-choice test is offered at the school on the first day, or online. Other procedures typically include an interview and a written assignment that are assessed by the program’s teachers.

Most intensive English programs offer a placement test or a set of procedures to try and ensure that students are receiving instruction at an appropriate level. Minimally, a multiple-choice test is offered at the school on the first day, or online. Other procedures typically include an interview and a written assignment that are assessed by the program’s teachers.

Many IEPs are staffed by people who started out as classroom teachers. This can be a positive thing, but management skills – especially the skills of managing people – have to be learned. One important skill that can be challenging to learn is delegation. Knowing when and how to delegate is important for all academic directors, student services managers, and program coordinators. Here are some tips for delegating.

Many IEPs are staffed by people who started out as classroom teachers. This can be a positive thing, but management skills – especially the skills of managing people – have to be learned. One important skill that can be challenging to learn is delegation. Knowing when and how to delegate is important for all academic directors, student services managers, and program coordinators. Here are some tips for delegating. As competition for students increases, intensive English programs should consider the price of their program. The pricing decision must take into account the overhead and operating cost of the program, as well as revenue and margin goals. But a conscious pricing strategy also positions the program in relation to competitor programs. Prospective students evaluate the program price against the perceived value the program will have for them. Here are five examples of intensive English program pricing strategies I have encountered over the past few years, each of which exemplifies a pricing strategy that worked, or didn’t, for the program. Prices are for tuition for a four-week general English program.

As competition for students increases, intensive English programs should consider the price of their program. The pricing decision must take into account the overhead and operating cost of the program, as well as revenue and margin goals. But a conscious pricing strategy also positions the program in relation to competitor programs. Prospective students evaluate the program price against the perceived value the program will have for them. Here are five examples of intensive English program pricing strategies I have encountered over the past few years, each of which exemplifies a pricing strategy that worked, or didn’t, for the program. Prices are for tuition for a four-week general English program.

How much freedom do intensive English program (IEP) teachers have to design their courses, choose their materials, and teach to their interests? How much should they? These questions become ever more compelling as accreditation standards push programs to be accountable for their outcomes.

How much freedom do intensive English program (IEP) teachers have to design their courses, choose their materials, and teach to their interests? How much should they? These questions become ever more compelling as accreditation standards push programs to be accountable for their outcomes.

“Can keep up with an animated discussion, identifying accurately arguments supporting and opposing points of view.” “Can tell a story or describe something in a simple list of points.” If your program is using Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) descriptors as its outcomes statements, you’ll be familiar with ‘can-do’ statements like these.

“Can keep up with an animated discussion, identifying accurately arguments supporting and opposing points of view.” “Can tell a story or describe something in a simple list of points.” If your program is using Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) descriptors as its outcomes statements, you’ll be familiar with ‘can-do’ statements like these. There are few obligations for faculty and staff that cause knots in the stomach and departmental wrangling than preparing the accreditation self-study. It is often viewed as a burden, a distraction from everyone’s ‘real’ work, and a process of bureaucratic box-checking or of trying to fit the round peg of the program into the square hole of accreditation requirements.

There are few obligations for faculty and staff that cause knots in the stomach and departmental wrangling than preparing the accreditation self-study. It is often viewed as a burden, a distraction from everyone’s ‘real’ work, and a process of bureaucratic box-checking or of trying to fit the round peg of the program into the square hole of accreditation requirements.

For the past few years, ESL teachers have been pushed to focus their efforts on helping their students achieve ‘measurable objectives.’ Am I the only person who finds this a strange idea? Measuring something is a matter of determining how much of something there is. To measure, we need a unit of measurement: inches and feet, centimeters and meters, pounds and ounces, grams and kilograms. By agreeing on standardized units of measurement, we can determine, objectively, the quantity of something.

For the past few years, ESL teachers have been pushed to focus their efforts on helping their students achieve ‘measurable objectives.’ Am I the only person who finds this a strange idea? Measuring something is a matter of determining how much of something there is. To measure, we need a unit of measurement: inches and feet, centimeters and meters, pounds and ounces, grams and kilograms. By agreeing on standardized units of measurement, we can determine, objectively, the quantity of something. Wrapped up in the term ESL (English as a Second Language) is an assumption that language, above all, is what students need to succeed in an English-speaking environment. The same kind of assumption can be found in the name of the most popular standardized U.S. admissions test for international students, the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). The CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) lists levels of language proficiency by skill, and many ESL programs continue to organize their curricula on the basis of Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing skills. The field of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) is a major feeder discipline in ESL teacher preparation programs.

Wrapped up in the term ESL (English as a Second Language) is an assumption that language, above all, is what students need to succeed in an English-speaking environment. The same kind of assumption can be found in the name of the most popular standardized U.S. admissions test for international students, the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). The CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) lists levels of language proficiency by skill, and many ESL programs continue to organize their curricula on the basis of Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing skills. The field of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) is a major feeder discipline in ESL teacher preparation programs.