We’ve been hearing more and more about companies requiring employees to return to work at the office now that the COVID-19 era work-from-home mandates are no longer so compelling. There is pushback from many employees, who argue that they are more productive at home and appreciate freedom from the daily commute that wears on them and causes traffic congestion and pollution. For their part, companies argue that in-office work results in greater productivity and collaboration among employees. Possibly the relative effectiveness of in-person and remote work depends on the type of business. While a purely digital company like Dropbox has a ‘virtual first’ policy, allowing employees to work 100% remotely, some high-profile corporations such as Amazon and Google are requiring in-person attendance. Amazon’s justification is that in-person work “will strengthen company culture, collaboration, and mentorship” (1). On its hybrid three-days-a-week-in-person policy, a Google spokesperson stated, “(i)n-person collaboration is an important part of how we innovate and solve complex problems.” (2).

In performance-based workplaces that are common in the U.S. and many other industrialized countries, there is a strong emphasis on individual productivity, performance, and achievement. Ambitious employees strive for recognition in order to get ahead, and performance evaluation systems recognize merit based on the achievement of individual goals. Managers rightly try to motivate employees to do their best work, and identify, recognize, and reward the strongest contributors.

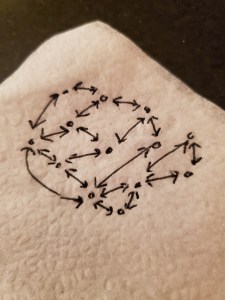

This isn’t where the manager’s role ends, though. Most organizations – and schools are a good example – don’t thrive through the isolated efforts of individuals, but through the joint work of people in collaboration, which is more than the sum of the parts. If an organization is in any sense like a machine (but let’s not stretch this analogy too far), then we know that the individual parts of a machine are useless on their own. It’s only when the parts are working together as part of a system that the machine functions. A big piece of the manager’s job is to ensure that the system – not only the individuals in it – is functioning correctly. This involves what I call ‘managing in the gaps,’ because it is about what happens in the spaces between and among the individual employees. When relationships are positive and there is collaboration, the team, department, branch, or organization is effective. Many problems organizations experience arise when relationships between and among individuals and teams are poor or not well developed.

Managers cannot simply trust that good relationships will arise in the workplace, and they should assume that at least some relationships between individuals and teams will be problematic. Even with great individuals on board, workplace setups can create friction that get personal. For example, at one intensive English program, it was one staff member’s job to provide administrative support to faculty coordinators of short and specialized programs. But because roles hadn’t been clearly demarcated, disputes frequently arose between the staff member and the coordinators over whose responsibility certain tasks were. The individuals involved were strong and positive employees who wanted to do a good job, but the situation inadvertently put them into conflict with each other, and yes, it got personal. It was the manager’s job to recognize the source of the tension and develop a solution, which in this case was to define and explain each person’s role more clearly, and follow up to make sure everyone involved understood. That done, relationships improved and programs could be delivered more effectively. This is an example of managing in the gaps.

Managing in the gaps isn’t only about troubleshooting problems, though; it’s primarily about preventing them from arising in the first place. Although it’s easy to criticize workplace meetings with slogans like ‘death by meeting’ and complaints such as, ‘I just want to get out of meetings and on with my job,’ there is a lot to be said for regular team check-in meetings and cross-department check-ins to hear what others are doing, share stories about what’s working or not, anticipate potential obstacles and plan around them, and just engage with each other face to face as people. Meetings like this don’t need a strict agenda, but should allow participants to share with others what’s going on in their job or area of the organization. Think of meetings like this as like bringing in your car for a regular oil change and tune-up. Again, the individuals in the organization may be doing a great job, but managers need to address the effectiveness of the whole.

While some online, work-from-home organizations have developed sophisticated means for the kind of relationship development and collaboration described here, people-centered organizations such as most schools don’t tend to lend themselves to the kind of collaboration needed to make the whole thing work remotely. From what we know about interactions on social media, at their most extreme people can become pretty nasty to each other when they don’t know each other or interact face to face. We are human, and most of our great achievements have come not from individuals working in solitude, but from doing things together, in relationship to each other. Some employees may argue, “I’m more productive working on my own at home,” and that may be true individually, but it’s what the team achieves – not the individual – that ultimately determines the fate of an organization.

Are you managing in the gaps? Here are six quick questions to check:

- When tensions arise between people or teams do you try to look beyond the individuals involved and consider the system that has put them into conflict with each other?

- Do you openly appreciate or celebrate collaboration among individuals and teams?

- Do you hire people based not only on their ability to do the tasks associated with their position but also on their ability to work with others?

- Do you evaluate, and reward people on the same basis?

- Do you regularly gather individuals on a team to check in on how things are going, even without a specific agenda?

- Do you call regular meetings of two or more teams to share what everyone is working on?

Make it a habit to pull back from the individuals – and from the individual team – and look for solutions in the gaps.

unimagined ways, but right now many educators face the immediate problem of how to respond appropriately to students’ use of ChatGPT, which can produce passable text and images in multiple genres and formats. What are we to make of this new resource and its place in education? Is ChatGPT a threat to academic integrity or a tool that teachers and their students can leverage to achieve better performance?

unimagined ways, but right now many educators face the immediate problem of how to respond appropriately to students’ use of ChatGPT, which can produce passable text and images in multiple genres and formats. What are we to make of this new resource and its place in education? Is ChatGPT a threat to academic integrity or a tool that teachers and their students can leverage to achieve better performance?

If you’ve been teaching English as a second or foreign language for a few years, you’ve probably taught using a wide variety of textbooks. Over the years, textbooks have evolved from layouts you could easily create (now anyway) in Microsoft Word, to sophisticated, full-color extravaganzas that seem designed to cater to limited modern attention spans. Textbooks also mirror evolving approaches to language teaching, from the decontextualized sentences of grammar-translation, through the drill-and-kill repetitions and substitutions of audiolingualism, information gaps and situational dialogues of communicative language teaching, to…whatever it is we have now, which is not entirely clear.

If you’ve been teaching English as a second or foreign language for a few years, you’ve probably taught using a wide variety of textbooks. Over the years, textbooks have evolved from layouts you could easily create (now anyway) in Microsoft Word, to sophisticated, full-color extravaganzas that seem designed to cater to limited modern attention spans. Textbooks also mirror evolving approaches to language teaching, from the decontextualized sentences of grammar-translation, through the drill-and-kill repetitions and substitutions of audiolingualism, information gaps and situational dialogues of communicative language teaching, to…whatever it is we have now, which is not entirely clear.

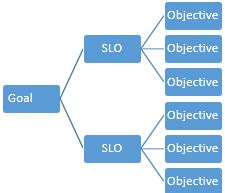

If you’ve had anything to do with curriculum over the past few years, then you’ve likely wrestled with the terms ‘goal,’ ‘outcome,’ and ‘objective.’ It’s not surprising they cause confusion. After all,

If you’ve had anything to do with curriculum over the past few years, then you’ve likely wrestled with the terms ‘goal,’ ‘outcome,’ and ‘objective.’ It’s not surprising they cause confusion. After all, Back in the day, if you were ‘teaching to the test,’ you weren’t really doing your job as a teacher. You isolated the pieces of knowledge and the skills that you knew would come up on the test and taught them to the exclusion of broader educational activities that might have enriched the students’ experience. You might have done this to ensure a high pass rate, which reflected well on you as a teacher if the higher-ups were judging you on your students’ test scores. But teaching to the test was frowned upon as a kind of shortcut for both teacher and students.

Back in the day, if you were ‘teaching to the test,’ you weren’t really doing your job as a teacher. You isolated the pieces of knowledge and the skills that you knew would come up on the test and taught them to the exclusion of broader educational activities that might have enriched the students’ experience. You might have done this to ensure a high pass rate, which reflected well on you as a teacher if the higher-ups were judging you on your students’ test scores. But teaching to the test was frowned upon as a kind of shortcut for both teacher and students. How many times are ESL students told to ‘go out and speak English?’ The possibility of using the target language outside the classroom and the school is surely one of the strongest rationales for learners to come to an English-speaking country to learn the language. Theorists of second language acquisition have proposed that ‘negotiation of meaning’ with native speakers will provide learners with the comprehensible input they need to make progress, making access to native speakers important to that progress. As Bonny Norton points out in the 2nd edition of her book Language and Identity, getting that access is not so simple.

How many times are ESL students told to ‘go out and speak English?’ The possibility of using the target language outside the classroom and the school is surely one of the strongest rationales for learners to come to an English-speaking country to learn the language. Theorists of second language acquisition have proposed that ‘negotiation of meaning’ with native speakers will provide learners with the comprehensible input they need to make progress, making access to native speakers important to that progress. As Bonny Norton points out in the 2nd edition of her book Language and Identity, getting that access is not so simple.

Wrapped up in the term ESL (English as a Second Language) is an assumption that language, above all, is what students need to succeed in an English-speaking environment. The same kind of assumption can be found in the name of the most popular standardized U.S. admissions test for international students, the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). The CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) lists levels of language proficiency by skill, and many ESL programs continue to organize their curricula on the basis of Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing skills. The field of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) is a major feeder discipline in ESL teacher preparation programs.

Wrapped up in the term ESL (English as a Second Language) is an assumption that language, above all, is what students need to succeed in an English-speaking environment. The same kind of assumption can be found in the name of the most popular standardized U.S. admissions test for international students, the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). The CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) lists levels of language proficiency by skill, and many ESL programs continue to organize their curricula on the basis of Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing skills. The field of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) is a major feeder discipline in ESL teacher preparation programs.